What is endometriosis?

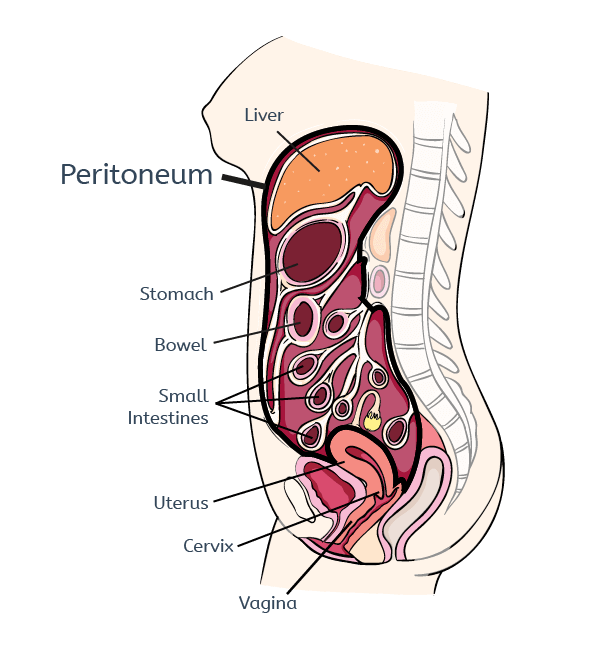

Endometriosis is a condition where the cells that form the lining of the uterus (endometrial cells) are found outside of the uterus, usually on the lining of the pelvic cavity or ovaries.

The cells attach and form deposits that are called 'endometriosis lesions.' Just like the lining of the uterus, the endometriosis lesions can grow and breakdown cyclically in response to ovarian hormones.

Endometriosis lesions survive in the pelvic cavity because they can develop their own blood supply that provides nutrients for the tissue. Endometriosis is common, affecting 6-10% of women in their reproductive years. In women that have pelvic pain and / or problems getting pregnant, this frequency increases to 35-50%.

Endometriosis is common, affecting 6-10% of women in their reproductive years

What are the symptoms of endometriosis?

Endometriosis is a chronic and sometimes debilitating condition that is associated with painful periods, but can also be associated with pelvic pain when a woman is not menstruating, or pain with sexual intercourse and when going to the toilet. It can also be linked with fatigue, bowel and bladder problems.

Women with endometriosis may also have difficulties becoming pregnant.

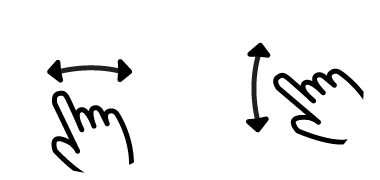

At the moment the only way to diagnose endometriosis is when a surgeon actually observes endometriosis lesions in the pelvic cavity of a patient. To do this a specialized keyhole surgery called a laparoscopy (see image below) will be performed. Because endometriosis can manifest itself in many different ways and shares some symptoms with other common conditions it can sometimes take a long time for women to be diagnosed with endometriosis.

What causes endometriosis?

It is thought that endometrial cells find their way into the pelvic cavity via a phenomenon known as 'retrograde menstruation'. This is where some of the cells from the upper layer of the endometrium that are shed during a period are refluxed back through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity. This occurs as a result of natural contractions of the uterus that expel endometrium during a period. Retrograde menstruation occurs in about 90% of women but only some develop endometriosis (about 10%). Endometriosis is a very complex condition and no one really knows the exact reason it occurs. However, there are a number of theories that scientific researchers are investigating. Some of these are discussed below:

1. Genetics

Women who have a sibling or mother that suffers from endometriosis are more likely to have the condition themselves, which suggests a heritable link. Large-scale genetic studies have identified a number of different genes that may be linked with endometriosis. However, researchers are still not sure how these genes may cause endometriosis.

2. Environmental pollutants

Pollutants may also influence the development of endometriosis, however a lot of the available evidence is contradictory.

3. Biological differences in the endometrium of women with endometriosis

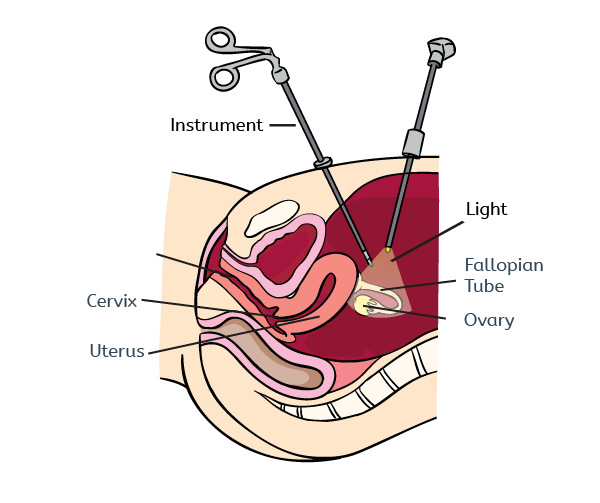

It is also thought that the endometrial lining of women with endometriosis could be different thus allowing it to attach to the peritoneal lining. For example, research has shown that in some women with endometriosis, there is an over-production of proteins responsible for tissue breakdown. This might be responsible for an increased ability of the cells to invade the lining of the peritoneal cavity. Increased production of proteins that promote growth and replication of cells has also been found in the endometrium of women with endometriosis. This may allow the tissue to have a growth advantage when it arrives in the peritoneal cavity. Researchers have also discovered that women with endometriosis produce more proteins that promote the growth of new blood vessels in the endometrium6. This suggests that when the endometrium is refluxed into the peritoneal cavity (see image below), it can easily attract new blood vessels allowing it to survive.

4. Immune system

Another possibility is that the immune cells present in the pelvic cavity of women with endometriosis are unable to clear away the endometrial cells. Specific immune cells called macrophages become activated in the pelvic cavity but they have a decreased ability to engulf and destroy the foreign tissue. Macrophages also act to encourage growth of the endometriosis lesions as well the recruitment of new blood vessels into the tissue. These important cells are also responsible for producing an inflammatory environment in the pelvic cavity which may actually contribute to pain in the condition.

Although a number of different theories exist about what causes endometriosis, it is likely that a combination of some or all of the above act to promote the development of the condition.

How can endometriosis be treated?

Currently, there is no cure for endometriosis. However, with the right treatment, the symptoms of endometriosis can be made more manageable.

The current treatments for endometriosis aim to reduce the severity of symptoms and improve quality of life. Treatment options available to women with endometriosis are pain relief, hormone treatments and surgical excision (usually key-hole surgery). Hormone therapies are used in the treatment of the condition to suppress ovarian function which limits the growth and activity of endometriosis lesions. If a doctor observes lesions during a diagnostic keyhole surgery, then the lesions will be removed. Recurrence of symptoms following treatment or surgery can be a huge problem in women with endometriosis. Repeat surgery will also likely be recommended to women that have recurrence of symptoms and wish to get pregnant since hormone treatments are also contraceptives. Given that current treatment options are limited and recurrence is such a problem, researchers are trying to learn more about the condition in order to find new ways of treating it.

Why does endometriosis cause pain?

Endometriosis is known as an inflammatory condition because lesions attract immune cells such as macrophages that create an inflammatory environment in the pelvic cavity. Nerve fibers that can detect pain actually grow into endometriosis lesions where they can sense the inflammatory environment. The nerve fibers then turn this information into signals that are transmitted to the spinal cord and then to the brain where pain is perceived. When nerve fibers are continually exposed to signals that activate them (which is the case for nerve fibers that grow into endometriosis lesions) then they can become hyperactive. This is thought to occur in endometriosis and this hyperactivity can lead to an enhanced perception of pain. Endometriosis may also cause pain because in some women the extent of lesions can cause compression of nerves or distortion of the pelvis, which can usually be relieved following surgery. See image below to see common sites of endometriosis.

Why can endometriosis affect fertility?

It is estimated that 60-70% of women with endometriosis are fertile and can get pregnant spontaneously and have children. Of the women with fertility problems, a proportion will get pregnant, but often only after medical assistance - either surgery with removal of the endometriosis lesions or medically assisted reproduction (IVF).

Endometriosis may cause reduced fertility because the inflammation present in the pelvic cavity could have a negative impact on sperm function, fertilization or implantation of the embryo. The changes in the production of certain proteins in the endometrium of women with endometriosis may also have a negative effect on fertility. Additionally, the reproductive tract of women who have many lesions and adhesions may become distorted, however, this can often be relieved following disease reduction surgery.

What are researchers doing to try and help women with endometriosis?

An important area of endometriosis research is biomarker discovery. A biomarker is a gene or protein that can be detected in a body fluid or endometrial biopsy (non-surgical) that is specifically linked with the condition. This will allow quicker diagnosis of the condition without surgery. Currently, the most effective medical treatment for endometriosis is ovarian suppression, which is associated with unwanted symptoms because it mimics premature menopause and is also contraceptive. Researchers are therefore trying to discovery new non-hormonal therapies for endometriosis. An ideal treatment would reduce or prevent the growth of endometriosis lesions, target endometriosis-associated pain and be fertility sparing.

Advice if you think you may have endometriosis

Because the symptoms of endometriosis are wide-ranging and share some similarities with other conditions, it is important to share as much information with your doctor as possible. One way to ensure you remember all the important information about your symptoms is to keep a pain and symptoms diary. If you have a history of endometriosis in the family, make sure you tell your doctor.

1. Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet 364, 1789-1799 (2004).

2. Giudice LC. Clinical practice. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 362, 2389-2398 (2010).

3. Hadfield R, Mardon H, Barlow D, Kennedy S. Delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a survey of women from the USA and the UK. Hum Reprod 11, 878-880 (1996).

4. Osteen KG, Keller NR, Feltus FA, Melner MH. Paracrine regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression in the normal human endometrium. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation 48 Suppl 1, 2-13 (1999).

5. Sugawara J, Fukaya T, Murakami T, Yoshida H, Yajima A. Increased secretion of hepatocyte growth factor by eutopic endometrial stromal cells in women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 68, 468-472 (1997).

6. Taylor RN, Lebovic DI, Mueller MD. Angiogenic factors in endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 955, 89-100; discussion 118, 396-406 (2002).

7. Chuang PC, Lin YJ, Wu MH, Wing LY, Shoji Y, Tsai SJ. Inhibition of CD36-dependent phagocytosis by prostaglandin E2 contributes to the development of endometriosis. Am J Pathol 176, 850-860 (2010).

8. Bacci M, et al. Macrophages are alternatively activated in patients with endometriosis and required for growth and vascularization of lesions in a mouse model of disease. Am J Pathol 175, 547-556 (2009).

9. Kennedy S, et al. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod 20, 2698-2704 (2005).

10. Dunselman GA, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 29, 400-412 (2014).

11. Stratton P, Berkley KJ. Chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis: translational evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update 17, 327-346 (2011).